Why You Shouldn’t Fight Elephants

It is several days after Halloween, which means a few things. The air is turning colder, people are suddenly feeling like soup as a whole meal, and my entire inflamed body is in active revolt from me subsisting mainly on small pieces of candy that I eat through the day.

My children are in the goldilocks zone of attaining this nutritional poison. No longer stubby-legged and pitiful, they can cover a reasonable distance on Halloween night. They’re old enough to set out on their own into the unknowing darkness and forage for sustenance, be it Twix or Snickers.

Until this year, candy limits were set unintentionally by me. I would walk with them, get cold and tell them to stop. They had no recourse because I control the wifi. With my glory days of parental control well behind me, the only limit on their journey to diabetes is their ability to carry multiple backpacks full of candy.

This puts me in a conundrum. My dining room table currently displays a shameful bounty of sugar and salt. Me and my penchant for not wanting to die would be wise to steer clear of this buffet of the damned.

And yet here I am, writing to you amidst a veritable riptide of candy wrappers. My office smells of peanuts. You know how your teeth have ridges and defined separation between them? Mine is just a smooth block of caramel now. I am caramel.

Here’s the thing though, I don’t technically like candy all that much. It’s fun, I’ll indulge when the mood strikes me so. Most days though I prefer to kill myself with cheese or negative thinking.

Don’t sit there and pretend you don’t know this song. Maybe you don’t sing it with candy, but you sing it with something. Perhaps it’s procrastinating at work, carbs, or buying beanie babies. You do something stupid that you don’t want to do, and I bet you do it all the time.

Why would this be? The answer is one of the most sophisticated structures in our known universe, and it’s a total asshole.

Atop your neck sits a computer that’s been iterating and upgrading itself for over 4 million years. While it’s true, many of those years it was encased in the skull of a fucked up little shrew, the fact remains you have a mammal brain, and it’s pretty damn impressive, if not—as covered—a total asshole.

Portrait of an asshole: your brain over the years

Let’s look at a quick timeline that starts as a shrew and ends with you laying comatose on a futon covered in Kit Kat wrappers.

350 million years ago: things start popping out of the sea because the sea is terrifying

200 million years ago: first mammals begin to develop, looking a bit like a shrew. Brains start filling the entire skull because surprise! The land is also full of terrifying things and they’ll have to compete with them somehow.

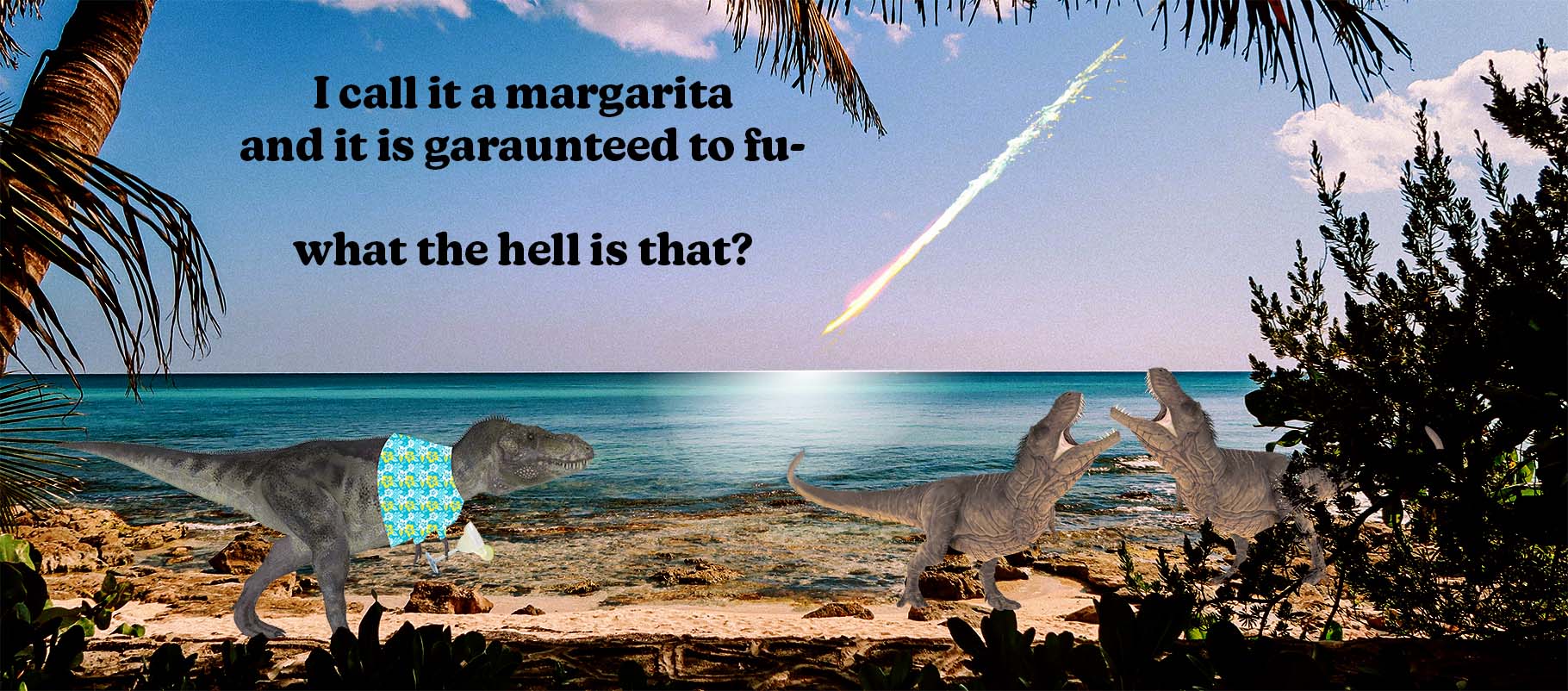

65 million years ago: SUCK IT DINOSAURS. HOPE YOU ENJOYED YOUR MEXICAN VACATION, SEE ANYTHING COOL? MAMMAL TIME, ASSHOLES. Mammals that survived the meteor strike take to the tree and will become the first primates.

14 million years ago: as primate social groups grow, so do the connections in the frontal part of the brain to manage the complexity. As an added benefit, other connections get juiced up as a result, and the information coming into the brain begins to be processed differently.

An ape emerges at this time. Branching off from this point is orangutans, gorillas, and chimps. All maintain a somewhat similarly sized brain.

2.5 million years ago: For an unknown reason, a series of changes begin and the brains in some primates start to grow. Probably a combination of stuff.

A mutation may have impacted jaw muscles, making the apes substantially less bad-ass, but gave their skulls room for brain expansion. Lame, but whatever.

Tools and fire possibly result from this, making the ape not only better at killing a ton of animals (getting more human!), but preparing food in a way that allows their guts to be more efficient, freeing up energy to develop the brain even further.

200,000 years ago: Once the brain became able to process rudimentary levels of speech, this planet didn’t stand a chance. By this point what we know as the modern human brain was taking shape. Our powers of reasoning, predicting, and planning became unmatched and we rightfully took the throne of animal most likely to destroy the entire planet over hurt feelings.

75,000 year ago: Pack your shit, we’re leaving Africa. Who likes potatoes and snow?

20,000 years ago: North America time.

12,000 years ago: Agriculture disrupts how we use the planet, ending our primary nomadic lifestyles.

The problem with the timeline

Timelines are often written out this way, and while technically true (insomuch as they can be given the amount we have to guess), they fail to articulate one crucial point: there’s a lot at the beginning of that timeline and very little at the end. It’s stacked in such a way that it gives the impression everything happened to a certain rhythm, when that’s definitely not the case.

When we get into millions–let alone hundreds of millions–our minds have a hard time grasping at the scale of it. To put it in a bit more perspective, let’s adjust our timeline. We’ll make it horizontal, and we’ll make it massive.

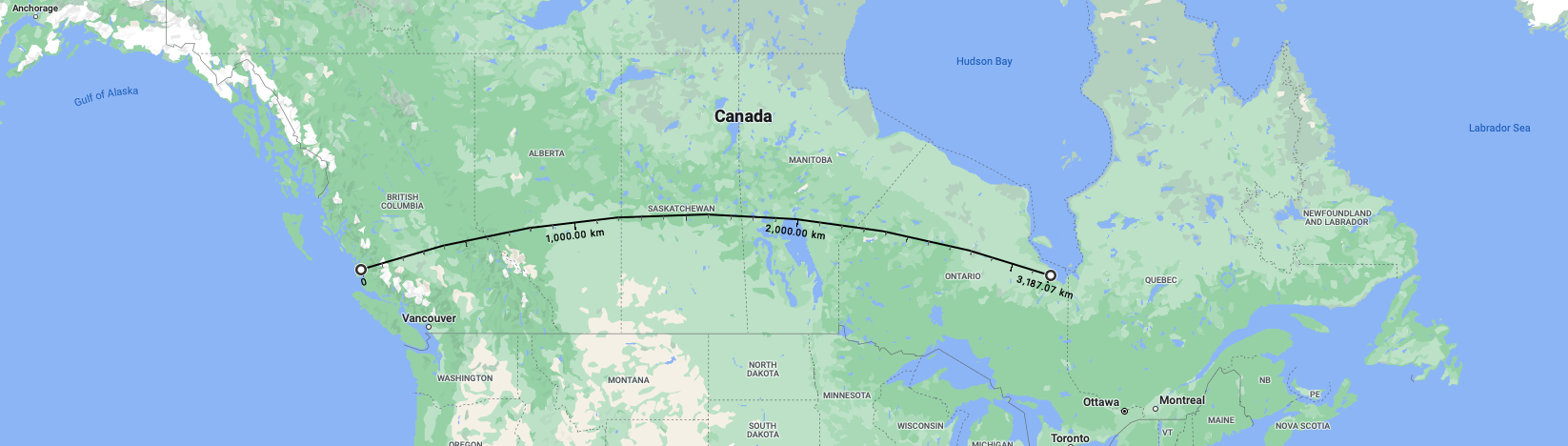

My first goal was to present this timeline to you with a horizontal line across the screen. After a few moments crunching the math, it became apparent this was a laughable attempt and we’d need something a bit bigger than the width of your screen.

Every year many unassuming Canadians make a critical error with their summer vacations: they set out to drive from one end of the country to the other. While many will tell you they don’t regret it, it’s a bit like parenthood in that to admit regret is to admit you wasted a huge chunk of time and resources, which makes us sad.

The drive in total takes about 73 hours. Honestly this makes what I’m trying to do here difficult because you’re not driving at a constant speed, nor are you driving in a straight line (you don’t even stay in Canada if you follow the most direct route). So let’s come up with a fantasy scenario where you’re going to drive from coast to coast in a perfectly straight line, travelling 100km/h (60mph) the entire time. This will give us an unheard of speed record to cross Canada, but math is hard so let’s make it easier on ourselves.

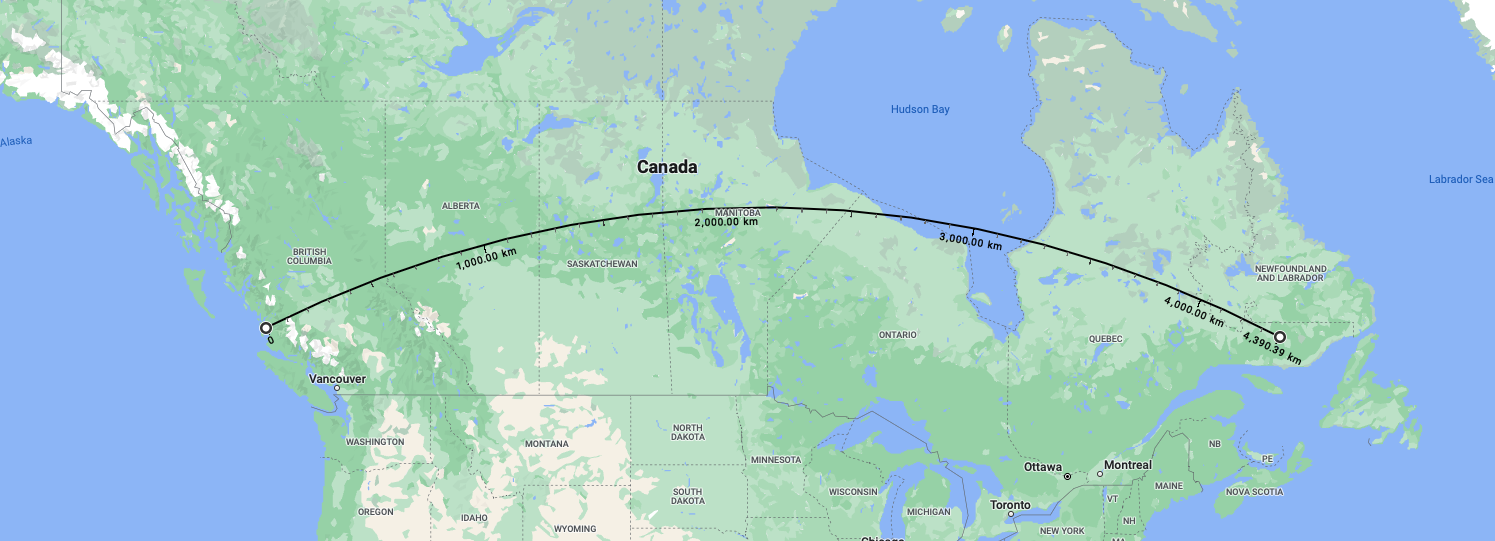

At a distance of 4720km wide (according to two somewhat arbitrary points selected on a Google map), it will take you about 47 hours to drive across the land of beavers and maple. For the Americans playing at home, think of the journey as going from San Francisco to NY City, then back to Indiana. Let’s say that width represents our timeline covering the emergence of mammals, until today. At what point do our milestones happen?

200 million years ago: We begin our journey just west of Vancouver where we pause to light a cop car on fire because the hockey team sucks. We’ll call this the beginning of mammal brain development (fitting).

65 million years ago: Dinosaurs die, making way for mammals.

We’re 3186 km into our journey but we’re about to be overtaken by a desire for poutine and cigarettes as we roll into Quebec. If you look at a map, it’s damn near 3/4 through our journey. Well played dinosaurs. Impressive run. Jog on though, because poutine is for closers and we’re fuelling our road trip with your bones.

14 Million years ago: Primates begin forming larger and more complex social groups.

4389km into our journey. Don’t forget to set your watches to something stupid, because you’re now in Newfoundland and Labrador, a place not content with only being confusing for being comprised of 2 individual places, but also the need to be in a timezone 30 minutes different from everybody else. Canada’s teenager… just difficult for the fun of it.

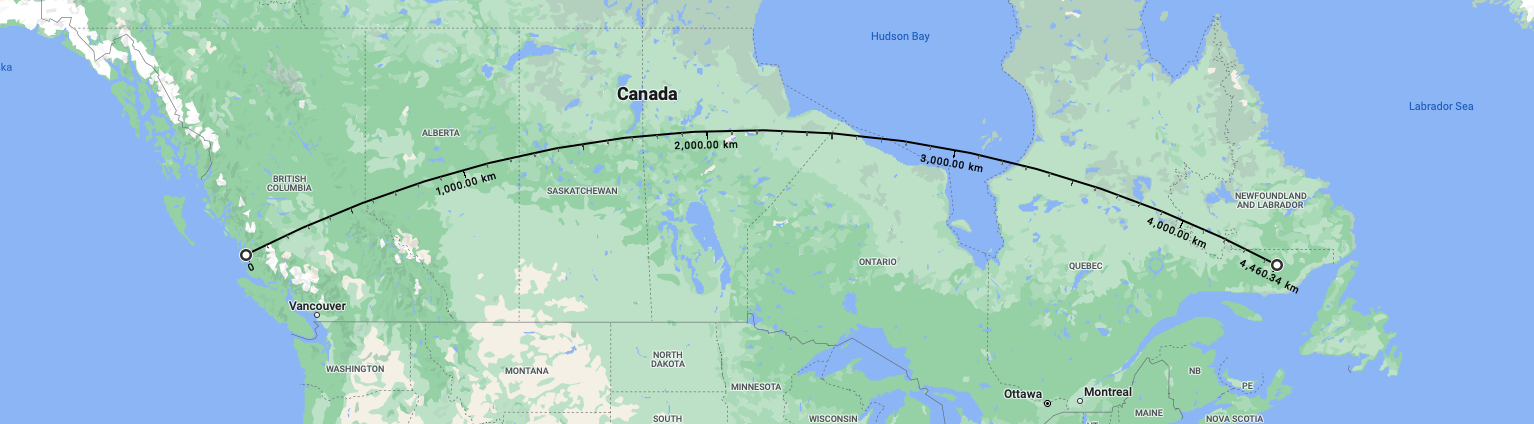

2.5 millions years ago: Primate brains start going off. Getting bigger and forming very powerful and important connections.

Distances are getting a lot less impressive as we complete 4661km. I used all my good Newfoundland and Labrador material in the previous point but we’re still here.

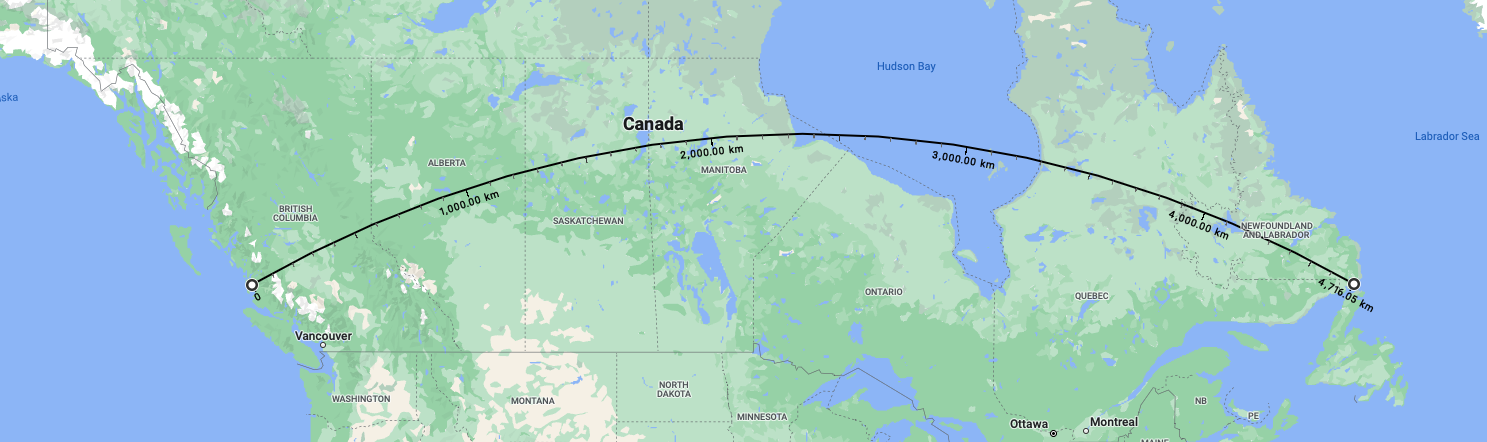

200,000 years ago: The sapien brain is close to what we know it as today.

Total distance on our journey? 4,715 km. We are now 4.7 km from our final destination. Our 47 hour drive only has 2 minutes and 49 seconds left in it. On the timescale of mammal brains, we’ve been human for 2 minutes and 49 seconds.

The point I’m over-emphasizing here is that while your brain is incredibly different from other mammals, all that incredible difference is a result of what’s happened in the last 0.1% of the last 200 million years. The first 99.9% of that 200 million years, we weren’t all that special compared to everything else.

What does any of this have to do with the diabetic coma I’m liable to slip into at any given moment from all this Halloween candy?

The parts of my brain that developed to keep me alive are incredibly old. The parts of my brain that developed to keep me happy, curious, starved for meaning, pining for your attention and avoiding twizzlers are incredibly new.

The problem I’m running into here is one of efficiency. Over that first 99.9% of cook time, the brain was slowly iterating and becoming more efficient. It uses the fuel we feed it brilliantly, almost to the point those parts seem to run without much attention at all.

The last 0.1% though? We developed the hell out of our neocortex. It’s the outermost layer of your brain and it’s so big in order to fit within your skull it had to fold itself up to save on space, which is why a human brain is all gross and bumpy while other animals have brains that are more smooth. This layer sets you apart (other smarty pants animals like dolphins have bumpy brains too but screw them). It helps you plan and strategize, learn from mistakes, coordinate groups, create farmland and financial systems. The issue? By being new, it isn’t efficient yet. It requires a massive percentage of your energy to operate, so it can become easily exhausted.

The Elephant and the Rider

The brain is a very complicated tapestry of modules, but for the sake of simplicity, let’s just pretend there’s two: the old and the new. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt coined the brilliant analogy to help us out with this, the elephant and the rider, which he explains thoroughly in his book “The Happiness Hypothesis“.

The old brain is the elephant. It concerns itself with your base needs, driven by instinct and emotion. The new brain (which conveniently sits atop it both in our metaphor and literally), is the rider. The rider strategizes, sees ahead, and infers what is to come based on what has come before. The elephant is endlessly strong, while the rider has a finite amount of energy. A fight between the two typically ends only one way.

One of the simplest ways to watch the elephant and the rider wage their one-sided disaster of a war is to follow diet trends. The often predatory diet industry is a multi-billion dollar one for a few reasons, not the least of which is that the entire thing is completely rigged. The industry relies on telling you that your rider is strong enough to defeat the elephant this time. You can out-willpower it, out-compete it, and push it around.

Numbers from weight loss attempts across decades suggest something different. With so many miracle diets on the market each year, isn’t it odd that success at keeping weight off over time is so unbelievably rare?

When your children bring home several pillow cases of candy, your elephant refuses to look at this as anything other than free fuel and free pleasure. Your rider meanwhile understands where we’re likely to end up. The candy is a terrible fuel which will leave you feeling possibly ill, it could wreak havoc upon your entire internal system, it may interfere with your sleep, and it may cause you to gain weight. The problem here isn’t that to avoid eating poorly it’s you vs. candy, but rather you vs. an endlessly motivated elephant.

How to kill a (metaphorical) elephant

Every year around January people speak of their New Year’s Resolutions. Quite often these resolutions involve something they hate about themselves. They think they’re too fat, or lazy, or unproductive, and this year is going to be different. To keep with the theme, they’re going on an elephant hunt. They don’t like where this bastard is going and it’s time to lift a big old floppy ear and give it a stern talking to.

Every year around February, people tend to learn how bad of an idea that was. The sad part is they often blame themselves, which is tragic because the fight was never fair to begin with. You go yell at an elephant and tell me how it ends.

This is a human problem, and to solve it we need a human solution. We were never the fastest or strongest but we’ve always been the most clever and social. While we can’t push it, we can trick it into going where we need it to go.

Use a Strong Fuel

If your rider isn’t running optimally, it probably can’t do shit against something that’s already so strong. The primary source of fuel will be sleep. Without at least 7 hours of sleep per night, you’re likely not going to be able to do much of anything overly well, let alone manage 200 million years of evolution trumpeting in your ear.

Pay attention to how quickly the elephant takes over the next time you’re running on low levels of sleep. Those instinctual desires will shine a little brighter and be harder to ignore when you’re low on energy.

Don’t Let the Elephant Fail

Remember, it wants to feel good and will change course if anything sucks too much. When you lean into a hard task and reflect on the learning available through failure, that’s your rider being all high and mighty. The elephant doesn’t play that game, it just moves on to the next thing that feels better.

This is in part why punishing workouts and diets so often fail. The desire to physically look differently loses its hold over you if the punishment goes on too long and irritates the elephant.

So when faced with a challenge, sometimes it’s worth it to give the elephant little wins. Break giant hairy tasks down into their component parts and get some little wins.

Use its power for good

Many people get to work by only doing 5 minutes of a task and then seeing what happens (which almost always ends up turning into more than 5 minutes). Typically once we get moving in the desired direction, the elephant finds a groove and then you can tap into its incredible well of energy. We often look at a massive task and become easily overwhelmed at the many requirements, when technically we only need to focus on the first.

In his book Atomic Habits, James Clear gives his own 2 minute rule. He refers to habits as the “entrance ramp to the highway”. The act of driving down the highway needn’t be a hours-long endeavour, technically it’s just a 15 second trip down the entrance ramp. The rest simply happens (in fact it may even be difficult to get off the highway sometimes). In fitness circles, this can sometimes be seen in the common phrase “the hardest part is putting on your shoes”. Once the shoes are on, the workout will happen more times than it won’t.

Clear’s two minute rule boils down to taking the ambitious task and forcibly breaking it down to two minutes. Wanting to train for a marathon becomes gathering your gear. Wanting to write a book becomes writing a paragraph. As touched on above, the elephant loves these sorts of tasks because they’re simple wins, while the rider loves these tasks because it’s easy to direct the elephant towards them.

Control the environment

You can’t necessarily direct the elephant down the path of your choosing, but you can cut down some trees to make certain paths more appealing. If there’s one thing humans kick a lot of ass at, it’s destroying trees, so let’s play to our strengths. This needn’t be an intense overhaul because the elephant more or less moves around automatically. For me, putting the bowl of halloween candy in a low part of the pantry is more than enough to keep it out of mind for most of the day. Will I eat 2 or 3? Bet your ass. Will I eat 15? Less likely.

This is the backbone to the rule “make desirable things 5% easier to do, and undesirable things 5% harder”. Remembering that the halloween bowl is behind the door requires the rider to recall it, and that guy is too busy doing other stuff.

Understanding the elephant for self compassion

When we understand what’s going on in the primitive areas of our brain, it can help us recognize more compassionate solutions to our problems. Punishing yourself at the gym or starving yourself on a diet isn’t just a poor strategy because the stats tell us so–it’s a poor strategy because you’re swimming upstream against millions of years of evolution.

Tragically, when many of us tap out of this unfair fight, we blame ourselves for not being good enough, smart enough, or strong enough. This only perpetuates the problem of not feeling like we’re enough, which typically is what got us into this mess in the first place.

Every day we make thousands of micro-decisions, and one problem many run into is the false belief that we are at the wheel of every one of them. When things don’t go the way we want them to, we’re quick to blame our bad choices or weak will. While some people find it uncomfortable, there is a degree of freedom to recognizing that many of our decisions are not fully arising with our consent.

Summary

The last 200,000 years have been so overwhelmingly turbulent for our brains, it’s not really all that shocking that people are positively freaking out these days. That time frame is but a pubic hair on the evolutionary timeline, and yet things appear to be moving at an ever-faster rate.

Cities and agriculture are only about 10,000 years old (0.5% of our 200,000 years), yet they’ve played a massive hand in what most people would say are baseline human things. Marriages, governments, philosophy, math, and financial systems are just beginning on the evolutionary timeline.

So when you see somebody have a breakdown in an airport or crying in a mall food court, they aren’t behaving all that oddly. Their brain is looking for a tree but it’s getting an advertisement to buy crypto. In short, everybody’s elephant is in a state of panic because none of this is familiar. While it’s common to say that the world is going haywire, it might be more accurate to say people are behaving perfectly normal for the environment we’ve created for ourselves.

As for me, I’ve conquered my candy issue using some of the points in this post. I dedicated myself to sleeping better this week, the bowl was moved out of a high traffic area, and I made some wiser food options a little easier to notice. Also I ate all of the Twix bars and that helped considerably.