Meet Your Brain’s Press Secretary

Have you ever watched a press secretary at work? This is more an American phenomenon, but all governments have them in one form or another. A group of journalists gather in a small room while a government official (the press secretary) stands at a podium and gives them the day’s news, followed by answering questions. Depending on whether you like the current administration, this event can range from logical to absolutely maddening.

When it’s maddening, this is partly because the press secretary is mostly full of shit. It’s not their fault. They aren’t dumb. It’s just that their job is to play dumb. Their job isn’t to deliver truth per se but to explain the current government’s agenda and reason for doing what they do. The flooding that ravaged the town? That’s why we have to act now on climate change. The school shooting? Just one more reason we need to make it easier for teachers to carry firearms. It doesn’t matter which team you cheer for; they all do it. And so do you.

Admitting you have a press secretary inside can be an uncomfortable pill to swallow. Nobody wants to admit there’s a part of them that bends and twists reality to fit our situation, and yet here we are, armed with some curious case studies and research to show that we are indeed quite full of shit. We like to believe that how we act aligns with how things are and how the world works (or is supposed to work). But, digging in–as we’ll do today–we can see that the truth is less black and white.

Meet the split-brain patients

Epilepsy is something of a problem. While seizures can come in several shapes and sizes, what we typically link to epilepsy is a spastic surge of jerky movement. Aside from them feeling terrible, the only safe place to ever have one would be in a padded room void of objects.

During a seizure, the brain’s e-brake malfunctions. Signals usually inhibited spread like greased lighting across the brain, sometimes resulting in violent convulsions. Think of the brain like an intricate traffic system of highways and side roads, all moderated with signage and traffic lights. A seizure removes all signage and traffic lights and puts rocket fuel in the cars.

Now imagine you’re put in charge of fixing this problem. The rocket cars are causing significant damage, so you might have to get aggressive. One possible solution might be to find the most prominent, widest road the rocket cars use to get across town and blow it to hell. If this sounds like a good idea, you’d make an excellent brain surgeon in the 1940s because that’s more or less what they came up with.

The corpus callosum is a bundle of nerve fibres connecting your brain’s right and left hemispheres. If a signal is to get from one side to the other (a common occurrence), it’s using the corpus callosum as the highway to get it done. As this highway became a problem when the signals went haywire, doctors began cutting the connection surgically.

This was a dramatic solution, but in the fringe cases when epilepsy couldn’t be managed with medication, it was the only solution remaining. What’s most messed up about the procedure is despite cutting what seems like a critical piece of infrastructure, it didn’t appear to impact the patients as severely as you might think. They went on to do regular tasks and hold down jobs and families just as they did before. Nothing seemed all that off.

For about thirty years.

Left brain and right brain

Traditionally, it was thought that everything had a place in the brain, existing on the right or left. Further, people might be “better” on one side. For example, a child prone to music might be said to be “right-brained,” while one who excels at math might be “left-brained.” This idea is mainly shit though; a remnant of an oversimplified theory that there is one spot on the brain for each skill you possess. What’s changed over time is the understanding that while there are areas where specific skills are primarily localized, the brain is more a network of modules that work together, and those modules are spread across the brain.

So while the left-brain-right-brain stuff was overblown, the guy who came up with the whole idea showed some bonkers results with split-brain patients (those with their corpus callosum cut).

One crucial fact about the brain that has held up better: the wires for the brain and the body cross at various points. What you see in your left eye is processed in the right hemisphere of your brain. If we drive a railroad spike into the right hemisphere of your brain, we’ll observe some problems on the left side of your body (amongst a few other things, like death, probably).

Finding the difference

Split-brain patients–despite having the main highway between the two hemispheres broken–still managed to get along in life relatively well. On the surface, most people wouldn’t notice a big problem until something very specific was tested. This is partly for a couple of reasons: for starters, signals can still get from one side to the other (albeit through weaker/slower connections). Secondly, most of the time, the patients were experiencing the world with two of most things (like eyes and ears), which ensured the signals were travelling to all the places they needed to be to make a “picture” of the world.

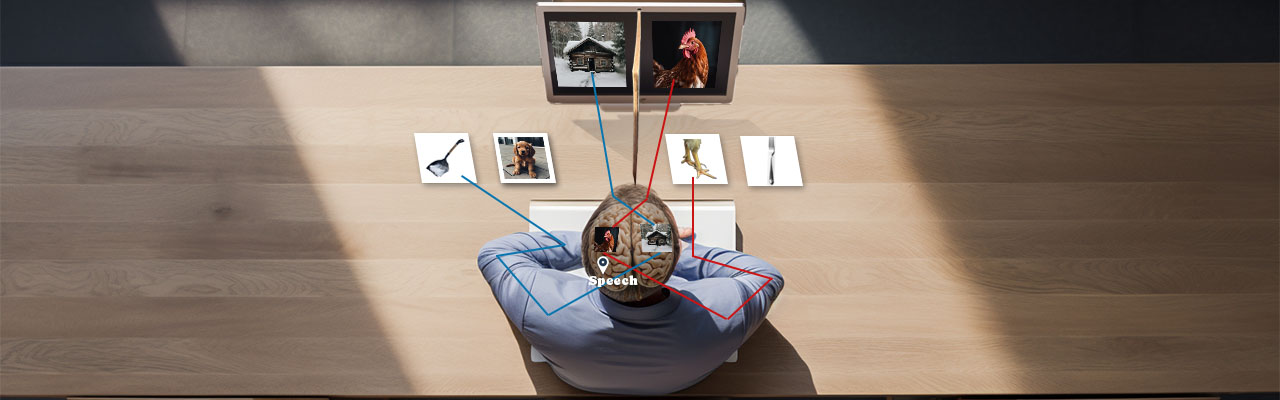

What would happen if they didn’t? Researchers conducted experiments where split-brain patients were shown things in isolation, meaning they were only displayed to a single eye or ear. This means the signals would end up being interpreted in one hemisphere but unable to transfer to the other for further processing. So, for example, if we show an image to the left eye only, the signal goes to the right hemisphere. This is fine because both hemispheres can process vision. Speech, on the other hand, gets a little trickier, as it’s predominantly on the left side. So if we show an image that ends up on the right side only, then ask the person to describe what they see, things start to break down.

Chicken shit liars

Perhaps my favourite experiment in the entirety of psychology is the chicken shit experiment. No, it’s absolutely not known as that, but in the absence of a snappy title, that’s what I call it.

Because the brain has the obnoxious quality of flipping everything, this might get convoluted, but stick with me (helpful/potentially confusing diagram below). A barrier is set up on the bridge of the nose so that test subjects can look at two different pictures, each one isolated to a different eye.

The left hemisphere processed a picture of a chicken, while the right hemisphere processed an image of a snowy field. Seeing as the right hemisphere (snowy field) controls the left side of the body, when researchers asked the participant to point with their left hand to a photo that goes with what they saw, they pointed to a shovel because you might use a shovel to clear snow.

Here’s where things get sorta weird. When asked why they chose the shovel, the split-brain patient runs into a problem. The area that processes speech and explanation is located in the left hemisphere, which didn’t process the snowy picture (it got a chicken instead). So as far as the left hemisphere is concerned, there wasn’t a snowy picture.

So what does the person say? There’s a kink in the line here. The two sides have vastly different information, but they can’t communicate. You might think the appropriate response here should be, “I don’t know why I picked the shovel.” You’d be incorrect, though; what happens instead is where things get much weirder.

“Shovels are used for cleaning out a chicken coop.” That’s the answer given—a goddamned lie. Everyone knows why the participant chose the shovel except the part of the participant’s brain that needs to explain it. Instead of being confused and offering a shrug, it confidently and proudly made up a reason. It wasn’t a deception or an attempt to pull one over on the researchers but rather a statement of pure belief.

Sometimes you just need coke

This experiment was then run in a different way using audio. The researchers ran participants through a simple study that meant nothing and had the participants wear headphones. At some point, the participant was instructed to stand up and walk towards the door through the left channel of the headphones (meaning only the left ear heard it, sending the signal to the right hemisphere).

Once the participant got up and walked towards the door, they were asked what they were doing and why. Again, this is asking a question of the left hemisphere that only the right hemisphere knows the answer to. Rather than saying any number of things ranging from “because that’s what you said, weirdo” to “fucked if I know,” they again made something up. “I just want to grab a Coke,” the participant replied.

Interesting timing. You could give them the benefit of the doubt and say perhaps the person legitimately wanted to grab a Coke at that point, but it doesn’t make sense that every other participant had some odd excuse in the same manner. Sometimes their knee was acting up; sometimes they just needed a bit of fresh air… there was always a reason, but it was never “because you told me to.”

Now, we do need to exercise a bit of caution. Studying people with massive brain trauma and saying they explain human behaviour in healthy people is understandably a bit of a stretch. However, it offers a fascinating potential explanation of something most of us see day in and day out.

The explanation is this: your brain has what’s commonly referred to as an “interpreter module” that’s networked throughout your brain to provide a story for why you do what you do. A press secretary, if you will. Something that sits by and puts a spin on everything you do. Why you broke up with that person, why you told your boss that thing, and why you like lobster. Is any of it true? There’s good reason to think it’s no different than getting up to grab a Coke. You did want that Coke… right?

And don’t tell me you don’t witness this every day. The difference is you think people are willfully lying to your face. Your friend who’s afraid of commitment conveniently (and suddenly) can’t stand their partner’s political affiliation and determines this is unmanageable and breaks things off right around the time they should probably propose. Your mother, who avoids conflict at all costs, can’t bear to make it to Christmas at your Aunt’s house because of COVID concerns (which she tells you over lunch in a crowded restaurant). “That’s bullshit,” you complain to your partner later that night. “Jim is terrified of making life changes, and Mom has been uncomfortable at her sister’s house since they had that argument.” It’s borderline offensive when people lie so poorly and directly to your face! Like you’re some idiot!

But what if they weren’t lying or weren’t aware they were lying? What if, just like that split-brain person going to find a Coke or thinking about chicken coops, they 100% believed what they were saying? You know… like what you do all day long with everything you do when you explain stuff away.

Are “we” the press secretary?

One of the messier questions in all this (points at everything) appears to be: who are you? If you try to answer the question, you’ll no doubt develop a series of statements backed by thoughts and feelings. You have certain convictions and beliefs about how the world ought to work. You’re a person who believes it’s essential to help people in need, vote for the <insert political party> party, and when somebody sends you a gift, goddammit, you send a thank you card back like a decent person. Don’t many of these sound like–oh, I don’t know–a press secretary? Long time fans of the blog (of which there are tens) might recognize another common name for this story-teller: the elephant rider.

This gets a little bit harder to prove scientifically. I’ll admit, it’s hard to back up with anything not resembling anecdotal evidence, but I believe there’s a case to be made that what we call “we” is little more than a bunch of little press secretaries all weaving the story of “you.”

It has earthy tones, like maybe pine and bullshit

The world of wine tasting is one I love to attack when I want to be a smug asshole to my friends who like wine. Sue me. I love ruining their fun sometimes. Ok, fine, I don’t actually do that and any desire to do so is just misplaced sadness that I don’t drink and can’t join in their little hobby. In truth I find the world of wine fans fascinating. Wine is a subjective thing, more art than science.

That’s probably not what most of them would have you believe, though. To a wine super-fan, they’ll tell you up and down they can pick out hints of blueberry, that the crop had an early frost, or if the farmer was emotionally abusive to the grapes. In reality, once we remove factors like the label, price, and country of origin, identifying aspects of wine becomes much trickier. Further, these factors greatly influence whether people even enjoy the wine. When I really want to drop a grenade and clear a room of my dearest friends, I bring up that many people can’t even tell a red from a white in a blind taste test.

While I’m poking fun at wine people, I don’t mean to be rude. On the contrary, I’m overly happy they derive so much pleasure from something. It also happens to be an outstanding example of an experience driven mainly by the internal story unravelling in real-time within our heads, told by a well-dressed press secretary with purple lips leaning on a podium bragging about how much their wine costs.

If you think real hard, this detergent will ruin your clothes

The marketing world has understood the press secretary longer than most, even if they don’t fully realize it. Perhaps they didn’t name it that, but the concept that people will live and die for a brand based on a fancy package or a snappy name is well known.

In one oft-cited study, participants were given three different detergents, all packaged in boxes with different designs and colours. But, of course, the detergents were all identical; the only difference was the boxes that carried them.

Participants noticed significant differences in the soap’s quality. Some even went so far as to say that one of the detergents damaged their clothing.

So, is everyone an idiot and a liar?

If anything, my agenda with this post isn’t to show how people are morons but to show you that we are easily fooled by design. Every day we’re bombarded with information, and without something to help us make sense of it all, we’d be perpetually overwhelmed. That something is our press secretary, and whether or not it gets the story correct is not the assignment. Instead, it exists to get you through life and manage as best you can. Truth is lovely, but sometimes truth gets in the way and makes stuff hard.

We can perhaps use the understanding of the press secretary to find an ounce of compassion for our fellow humans. It’s easy to lose faith in each other or feel like everybody is thrashing madly in a sea of incompetence as we calmly paddle by in our dingy of wisdom. Vaccines, naturopathic medicine, economics, astrology, politics, moon landings, gun control, racism, climate change, sexism, and the shape of our planet… these topics drive people insane. How could anybody possibly entertain the idea that <thing you don’t believe in goes here>?

When we dig though, we see that self-deception is not just the realm of the uneducated or the hate-filled. It’s a part of our operating system that builds our experience. We can all be deceived; it’s just hard to recognize when it’s happening to us because that’s what deception is.

A common thread through the split-brain experiences, wine tastings, and detergent tomfoolery is that nobody lied purposefully. Nobody was consciously trying to trick anybody else; they believed in their hearts that their actions were on the level. It’s easy to see people who disagree with us as having an agenda or ignoring obvious facts for their own gain. But, instead, there’s plenty of evidence that they think you’re the one ignoring reality.

Summary

Every day you take in an unmanageable amount of information. Every interaction, win, and loss brings a potential lesson for how the world works. It’s the job of your press secretary to weave it all into a coherent narrative to help you navigate existence. While we typically treat this story as a textbook of truth, it’s probably more an incredible work of fiction that keeps the pain down and the chance of survival up.

We can see that when we stop the brain from networking correctly, the story maker becomes more apparent. When they don’t have access to all the information, the stories don’t stop as we might expect; instead, they continue (confidently) in new and confusing directions.

While more challenging to recognize, we can see these directions most easily in the friends and family we know best. You, as a casual observer with insider knowledge, can easily see through their self-deceptions.

It would be unlikely that everybody is off their rocker except us. The most likely scenario is we lie just as much as everybody else; we’re just unable to recognize it because we’re too close to it. More bluntly, it is quite possible that the person we call “I” is the storyteller, the press secretary holding court and explaining everything.

With this understanding, we can hopefully find compassion for our fellow humans. As differences continue dividing and enraging us, perhaps we can take a solitary moment and realize that we are not entirely rational. We’re all just a knotted ball of experiences and lessons, incorrectly interpreted to keep us safe every step of the way.

Sometimes the goal is merely to recognize. By noticing that the press secretary is confidently spouting off what it has very little idea about, we can introduce an air gap between our thoughts and actions. In that gap, we can find a quiet moment to make a more informed decision about how we want to proceed. Sometimes they know best, but sometimes they do not, and knowing that they exist allows us to decide if we’ll listen to them.