From Scattered to Focused: Building a Focus Trigger with Josh Waitzkin

Josh Waitzkin often comes up in performance circles because, unlike many wannabes, he walks the walk in extraordinary ways. He preaches performance, and he appears to succeed at near-everything he does. Within his formula for success is a way of living that is effective and adaptable across disciplines.

In Josh’s highly-recommended book “The Art of Learning,” he outlines not only his story, but the interconnected skills and mindsets that led to him becoming a person who excels at things. He thinks a little differently and he does a beautiful job explaining how. One example he points to is how he built his focus trigger–a way to quickly drop into a zone of focus whenever he needed it. The best part? It’s not overly complicated, and something we can all adopt.

Josh Waitzkin Had a Problem with the Russians

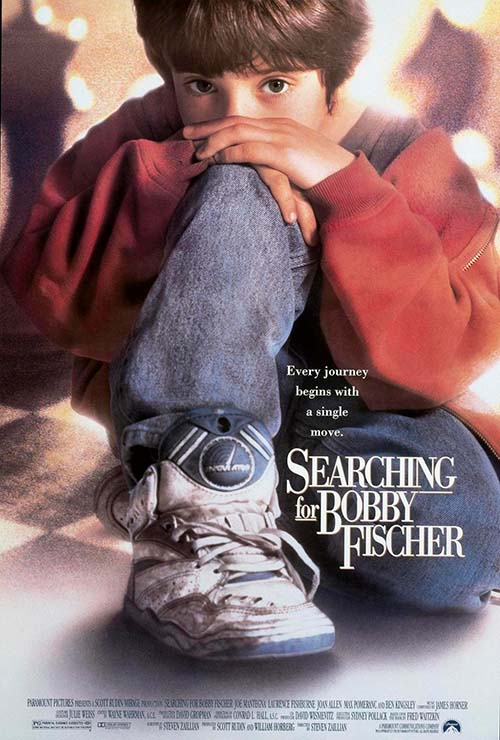

If you’re a fan of 90s cinema, there’s a reasonable chance you already know who Josh Waitzkin is. You may not know the name, but perhaps you know him as this:

As a child, I naturally assumed the kid on the movie poster was supposed to be Bobby Fischer. I only knew three things about the movie: It’s about chess, Bobby Fischer played chess, and I had zero interest in watching a film about chess. Due to that last point, I didn’t realize the kid in the movie poster is Josh Waitzkin, a young chess prodigy who became a National Junior Chess Champion at nine. Sorry for the spoiler. You’ve had thirty years.

The movie’s title threw me off because it’s not about Bobby Fischer, but rather his father (author of the book the film is based on) was comparing his son to Bobby Fischer, a child chess prodigy from the 50s.

The movie explores what it was like for Josh to compete at such a young age, but to me, the more interesting story happened after the movie’s events. As a teenager, he began to face some interesting challenges that would set him on a path to becoming curiously good at other parts of his life.

One such problem was with Russia. Well, Russians. Russian children, technically. As the Soviet Union fell, Russian chess players began showing up in the United States, along with their bags of tricks. If Rocky IV and the Olympic Games in Sochi have taught us anything, it’s that Russians like to win perhaps more than is necessary. Some might even say they cheat like crazy. Would I say that? <REDACTED>.

In chess, the bag of tricks the Russians brought over were psychological moves ranging from clever to outright bullshit. Josh’s first exposure to this was a nearly imperceptible move from an opponent he could never quite figure out. It wasn’t until somebody took his father aside and shared the trick: the Russian kid would subtly tap a chess piece on the side of the table, throwing off the cadence of his opponent’s mind. This would later be understood as a remnant of old Soviet research on hypnosis and mind control.

The tricks would amp up from there, becoming less subtle at every turn. One opponent would straight-up kick Josh under the table during tense moments. I guess the governing body of chess didn’t have many rules in place for physical altercations because it’s fucking chess.

… and then the Taiwanese

Seriously. Nations of the world. Stop cheating.

Josh’s story doesn’t end with chess. Upon leaving chess behind, he would take up martial arts. Using the lessons he’d learned from being a child chess prodigy, he began to explore other areas of interest, and he found many of the skills transferrable (perhaps the unexpected role of kicking in chess helped him here).

As he climbed the ranks of Tai Chi Chuan Push Hands (here you go), he became good enough to participate in national championships. That meant travelling, and one such tournament took him to Taiwan.

The Taiwanese competitors had home advantage and used every bit of it. Schedules would curiously change randomly for the out-of-town competitors, and the meals offered were greasy and heavy. Josh would show up to his matches unexpectedly with a scattered mind, full of improper food that was eaten at the wrong time. His opponent, meanwhile, would be well-prepped and ready to rock (because he knew when the match actually started).

This frustration would drive many to quit. When it happened in the chess arena against the Russians, many American competitors did. Josh is a weird duck though, and he became interested in the tricks and how to counter them (a good indication of why he’s so good at chess and martial arts).

What became apparent to Josh during this time was that the world would not accommodate him. When we require preparation and quiet, it will become random and noisy. We will not get what we need, so flexibility is the wiser skill to develop. He puts it:

“You are concentrated on the task at hand, whether it be a piece of music, a legal brief, a financial document, driving a car, anything. Then something happens. Maybe your spouse comes home, your baby wakes up and starts screaming, your boss calls you with an unreasonable demand, a truck has a blowout in front of you. The nature of your state of concentration will determine the first phase of your reaction—if you are tense, with your fingers jammed in your ears and your whole body straining to fight off distraction, then you are in a Hard Zone that demands a cooperative world for you to function. Like a dry twig, you are brittle, ready to snap under pressure. The alternative is for you to be quietly, intensely focused, apparently relaxed with a serene look on your face, but inside all the mental juices are churning. You flow with whatever comes, integrating every ripple of life into your creative moment. This Soft Zone is resilient, like a flexible blade of grass that can move with and survive hurricane-force winds.”

Building the focus trigger

The solution for Josh was to construct what he calls a “trigger” to bring him where he needs to be. Regardless of what the world (or its annoying inhabitants) throws at him, he would develop a routine of actions that would centre him and give him the best chance at instant preparedness.

The first stage is to identify what in life brings you closest to a serene focus. What do you do that makes time slip away? In the book, Josh coaches a man who identifies his serene focus as playing catch with his son. It turns into a moment of pure connectedness for both of them and something that is entirely relaxing for body and mind.

The next step is to develop a series of behaviours that can be done leading up to the serene task. It can be any number of healthy behaviours. For the man Josh works with, it ends up being a light snack, meditation, stretching, and listening to music. He would perform this pleasant series of behaviours before slipping into his favourite action (playing catch).

After performing this entire routine several times, the next step is to swap out the serene end-point with whatever is important in that moment. Playing catch turns into the big meeting, sitting down to complete the report, or going for a hike.

What ends up happening is a subtle bit of trickery. The mind becomes primed for focus, which catalyzes proper performance. You’ll do everything better with focus and clarity, and this is merely a way to give that focus less friction to appear.

Once you’ve established your focus trigger, the next stage is to up the efficiency. Moving gradually, adjust a single step in the routine to be easier to complete. Maybe shave 3 minutes off a meditation, or swap out the snack for something easier to obtain. Whatever it is, the only rules are it must get shorter/easier and you must move very slowly.

Over time with enough optimization, the entire routine can be shortened to a single string of movements that trigger the mind into a state of pure focus.

What’s going on in the brain when we use a focus trigger?

Maple-syrup-chugging Neuroscientist Donald Hebb from the Great White North gave us “Hebb’s Law.” While he didn’t coin it, the law was distilled into a beautiful little rhyme, stating, “Cells that fire together, wire together.” While it feels painfully obvious, this law is a critical piece of how we learn. It’s also highly transferrable, as touched on in the post on remaining in the present moment, even when the present moment sucks.

To oversimplify things, neurons in your brain need to stimulate neighbouring neurons, creating a cascading signal, which results in you doing the thing. If those pathways get lit up repeatedly, the signal travels with less and less resistance each time. In the same way a sled first travels down a hill slowly as pathways in the snow are created, but it moves faster as the tracks become more established, signals in your brain travel along well-worn routes easier.

This principle helps us understand what’s happening when we build a trigger to find focus. We’re sitting at the top of the hill, and we carve out a path to the goal at the bottom (in this case, focus). Over time we may manipulate the path slightly, perhaps finding a faster route to the goal, but the brain instantly recognizes what’s going on and says to itself, “Ah, we’re headed towards focus.” The cells that have been firing together are now wiring together, and what was once arduous is now completed with less effort.

A focus trigger for all things

You’re probably not a chess grandmaster, and I’m going to bet a silver dollar you’re sure as hell not competing in the national championship for Tai Chi Chun Push Hands. What you most likely are is a regular-ass human doing regular-ass things (probably with a great ass, though). You don’t need a focus trigger to reach Olympic-level glory or topple your chosen field.

I will make the argument, however, that you still need one. Why? Because focus isn’t merely for the high performers of the world. Focus is for all of us and benefits us in every walk of life. It seems the answer to almost all problems circles back to the nebulous “be present.” While we may understand the start point (the problem) and the endpoint (the solution), the path between the two is obnoxiously unclear.

Focus is a crucial ingredient in finding that present moment. Seeing things with clarity is a critical component of both handling high-pressure problems and enjoying a calm walk through the woods with your kids. It’s the gift that never stops giving, and the same focus trigger that allows Josh Waitzkin to win chess and martial arts tournaments is what can allow you to find meaning in the mundane.

Summary

At a young age, a very wise Josh Waitzkin realized that the world would not bend to his will, so he needed to learn to bend to it. By employing interest instead of frustration towards his opponents, he found calculated moves around their tricks by using ones of his own.

His first step was to identify a behaviour he adored, his second step was to build that behaviour into a routine that would make him less reactive, and his third step was to optimize that routine so that it could be practiced anywhere (and in short order when needed). This was how Josh built a focus trigger to help him with chess and martial arts, but also how he built a trigger to help him with the rest of this silly, silly life.

While the lessons of the hyper-performative may seem isolated to the world of athletics, they’re easily transferable to the rest of us. The ability to find the present moment and all the glories within comes from cultivating focus in a world that demands it be scattered.