Does Money Buy Happiness? The Pursuit, The People, and The Proof

Can money buy happiness? The question seems to raise a spirited and unending debate. It’s been explored in different forms since wealth was measured in fruit. In our relentless pursuit of prosperity, it’s common to wonder if the accumulation of resources correlates with an uptick in happiness.

Science has even taken a stab at finding the answer, albeit landing on the same mixed results. In a fascinating turn, 2023 saw two distinguished researchers, long-standing opponents in this debate, bridge their divide to understand the discrepancies in their data better. What they unearthed reaches far beyond a simple verdict on the purchasing power of happiness—it prompts a profound reevaluation of how we measure our well-being and the factors that colour our contentment.

It can’t buy happiness… right?

I’ve always been firm in the camp that money doesn’t buy happiness, which I’ve had to be because I don’t have a ton of it. It wasn’t always this way, though. My parents had me about a decade later than most others, so they were more established in their careers and hit on some success; so, as a family in a small town, we did pretty well financially (comparatively to others, which matters a lot). As a child I never felt the pinch of insecurity or the sadness of wanting. My Santa was efficient and listened very well, way better than everyone else’s Santa (who seemed asleep at the switch).

When I moved out and chose a career, the gravy train derailed, scattering lucrative and precious gravy all over the countryside. It was time to enter a new phase of life–one where Kraft Dinner was more a way of life than a lazy indulgence.

I’ve remained steadfast in my opinion around the money/happiness debate partly because I’ve always been relatively happy. Of course, I’ve wanted just a bit more money as everyone tends to occasionally, but I’ve remained relatively happy. If money equated to happiness, it seemed I should be on the lower end of the scale compared to almost everyone I knew, but that didn’t appear to be the case. I am, of course, 1 data point out of 8 billion.

A tricky debate

The debate is a difficult one to resolve for a few reasons. As financial writer Morgan Housel would put it, we think of money as something that lives in a cold, emotionless spreadsheet, when in fact, it fits better in the colourful and variable world of personal psychology. Feeling and emotion are so tightly wound with money that teasing them apart is impossible. How you feel about debt, risk, value, and prosperity is not black and white but a complex interplay of unique personal experience, fear, and success.

So go ahead and make the argument that money doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme, but don’t get overly offended if the single mother of 3 fighting daily to keep the heat on pulls a knife on you. Conversely, argue that you’d be happier if you could make an extra $20,000/year, but don’t be surprised if the surgeon making a quarter million a year who can barely get out of bed in the morning has a few things to say.

As author Mark Manson points out: “Money is like oxygen. When you have none, it solves every problem. When you have plenty, it solves none of your problems.”

What even is “happiness”

Another potential problem with the debate is we actually might not all be talking about the same thing. Happiness means different things to different people; even then, it’s easy to get our definitions tripped up.

For many people, when they’re talking about happiness, they’re talking about joy. They aren’t chasing happiness as much as that rollercoaster rush of excitement. Joy is undoubtedly an essential ingredient in the omelette of life, but it’s not something you want to be chasing exclusively. Joy is hot sauce. We definitely want it, but nobody is asking for a bowl of it.

Joy is fleeting, so by nature, it falls away. If we sat around constantly blissed out as so many of us wish, we’d never get anything done. Your brain works exceptionally hard to ensure you aren’t ever getting too happy, which feels like a dick move, but it’s more of a feature than a flaw (because it also works to ensure you aren’t ever getting too sad also).

In addition, we become accustomed to any drug, and internal drugs are no exception. A rush of joy is a rush of dopamine, and too many rushes of dopamine can mean you need more and more of it to achieve a base level of joy.

So, what is happiness? Happiness is probably much closer to a state of contentment or an absence of nagging problems. It’s not so much kayaking off a waterfall as it is simply watching the waterfall because you have nothing else you need to do. Happiness is far less sexy than joy.

The money/happiness plateau

Whether you’re aware of him or not, there is a strong likelihood you’ve heard Daniel Kahneman’s argument. In 2010, he and others published their findings on the relationship between increased money and happiness. The paper argued that happiness does increase along with money, but only until a certain point. While the magic number can’t be the same between all people, Kahneman ballparked it around $75,000 (USD). If you make less than that, growth towards that amount can feel outstanding, but beyond it, people tend to experience diminishing returns. Perhaps growth from $50,000 to $60,000 increases your happiness by 10%, but a jump from $150,000 to $160,000 might not even be noticed.

Good times… forever?

Meanwhile, Matthew Killingsworth ran a similar study but found a different result. By the time the dust had settled on his efforts, he felt he had evidence that the plateau wasn’t nearly as pronounced and that money and happiness go hand-in-hand and continue to grow together, up to $75,000 and beyond.

The debate was on, and over the years, both researchers would be pitted against one another, arguing that money’s impact is different. Whomever you agreed with was brilliant, and whomever you disagreed with was a hack and did a shitty study. So a typical scientific debate, really.

Proper-ass science

In a rare and beautiful move, the two researchers came together to determine why their numbers differed. By the end of their joint study, they had found a fascinating new factor in the money/happiness debate.

What seems to have set the two initial studies apart is that they inadvertently overlooked something critical: how happy you are before you get your money matters . While the studies reported that people either hit or did not hit a plateau of happiness, the question they both failed to answer the first time around is, “What if people are different?”

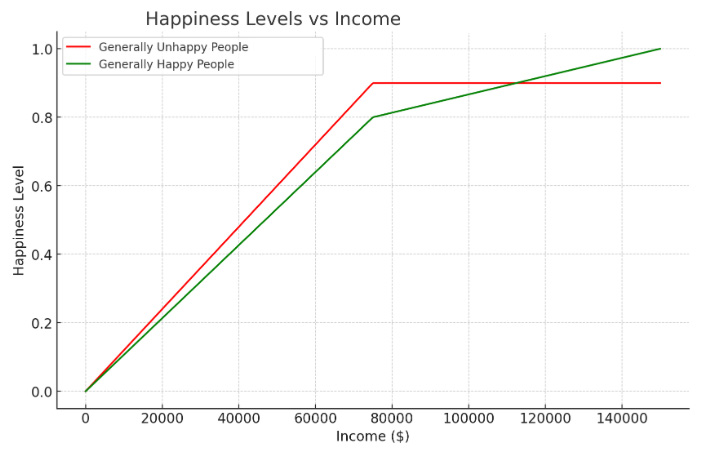

For people who aren’t typically all that happy, as money goes up, they get super happy, and then around the $75,000 mark, they hit the ceiling and their happiness levels abruptly flatline (this is what Kahneman found).

Meanwhile, for people who are typically happy, their happiness increases steadily with money. Their rise in happiness isn’t as pronounced as the unhappy group (they do have less distance to travel on the happiness scale, after all), but it tends to keep trucking beyond $75,000. It does seem to level off eventually, but not nearly as sharply as it does for the unhappy group.

I made a graph of this to illustrate it. Please don’t ever copy it anywhere because it’s a gross oversimplification, not their actual numbers, and completely made by me.

What Kahneman got wrong the first time

The issue appears to be in the way the study measured happiness. In the original Kahneman study that showed an abrupt plateau at $75,000, his questions were structured in such a way that they did a fantastic job of measuring the uptick from “unhappy” to “reasonably happy” but a less fantastic job of measuring the uptick from “reasonably happy” to “it’s-taco-night happy.”

Kahneman was detecting that unhappy people were hitting a happiness ceiling at $75,000, but he wasn’t detecting that the happy people were continuing to get happier.

What Killingsworth got wrong the first time

While Killingsworth’s original study did a better job of differentiating between happy and unhappy people, where he may have stumbled is in averaging everything out to obtain an “average person.” Despite what you think about that boring person at work who’s kinda dumb but mostly harmless, an “average person” doesn’t exist.

As discussed on his podcast “99% Invisible,” Roman Mars addressed the problem of average by using the military as an example. In the 1950s, the American military designed the cockpits of their planes to fit the average male body. You might think that taking measurements from thousands of men across ten categories would yield a measurement that many of them would fit into.

As it turned out, not a single one fit into it. By designing the cockpit to fit the “average man,” they inadvertently designed a cockpit that fit nobody at all. The solution was ultimately to design a cockpit that was adjustable to fit variable sizes because humans are too damn weird.

This is the same problem that Killingsworth ultimately ran into. The two groups interfered with the overall results. By looking at the average, he detected not only the sharp rise in the happiness of the unhappy people making below $75,000 but also the more steady increase beyond it in the happier group. Averaged out, the unhappy group’s sharp rise and flattening out became less apparent.

What does this mean for you?

The results of the joint study explain beautifully why this debate has raged on for so long unresolved. Not only is wealth intimately tangled up with unique experience and emotion, but disposition (of which we all vary) matters a lot.

It also raises an uncomfortable truth because whichever side of the debate you land on, you’re only 50% correct. You can buy happiness, and the pursuit of wealth is fruitless… both statements are factual, but only one will apply to you.

Team Happy Pants: a path forward

Should you find yourself insufferably optimistic and a proud member of Team Happy Pants, your path forward might be hilariously counter to your overall attitude toward money. That “eh, I don’t need much money to be happy” attitude? I’ll bet ya $20 you’re wrong.

While it’s not generally recommended that you chase riches at the expense of your friends and family, pursuing wealth for this group might not be all that crazy, providing you have the capacity to do so (and that capacity is a huge factor). Perhaps you might be happy enough to feel little necessity to go further, but the evidence does imply that if you kept going with it, your happiness would likely increase.

Team Grouchy Pants: a path forward

This one is more difficult, which is just how it goes for you pessimists. Fucking typical, right? WHAT ELSE IS NEW?

Unhappy people, by nature, tend to grasp happiness because it seems to evade them. As our society does an excellent job of convincing us that attaining stuff equals good times, it’s an easy trap to fall into.

The great news here for pessimists is that gaining wealth is relatively tricky. Perhaps for some it comes naturally, but for most of us it’s not overly simple. If you make more than the ballpark figure of $75,000, it’s a war you might be able to give up. The bonus here is if you haven’t yet attained $75,000 in income, you’re part of the group that can achieve the most substantial surge of happiness by getting there (suck it, Mr Brightside!).

But if you’re in this group and have attained that base income (and happiness is your goal), you can pursue other avenues. These avenues have the added benefit of being potentially healthier, more enjoyable, more accessible, and backed by science as legitimate ways to move your needle.

Moving your body, eating real food, having coffee with a friend, sleeping a bunch, or putting energy towards your core values will all likely pump-up your happiness in a way that money probably won’t.

Summary

Of course, none of this is guaranteed. As stated, our relationship with money is complicated, nuanced, and heavily reliant on our past experiences. What the joint study showed us was a trend, but it’s important to remember in all trends, there are outliers that don’t quite fit the mould. Maybe you’re mouldy? Wait, that came out wrong. Let me try again.

Indeed, Killingsworth’s original study fell prey to the problem of averaging everyone out. In a way, the new study improves upon that, but it’s still grouping people into boxes that people traditionally don’t always fit into.

But it does give some of us a potential thing to think about. Maybe you happen to fit into one of the categories and can relate. Perhaps you’re a generally happy person who’s avoided career advancement because the wisdom of the day is to avoid doing such a thing, or maybe you’re a stick-in-the-mud who keeps growing wealth only to find the happiness that accompanies it falls through your fingers? If you are, perhaps this study can encourage you to shake things up a bit and try another strategy. Science, after all, is all about trying new things and seeing what happens.

In the grand, often confusing dance between our bank accounts and our bliss, perhaps the promised land we all seek needn’t be found exclusively within our wallets. Whether you’re chasing champagne wishes or Kraft Dinner dreams, happiness does appear to be available to you. Perhaps we need to stop arguing which direction is right, and start asking which direction is right for us.